Published in Sea-Breezes magazine

by David Bray and Simon Adams

We have a breakfast bar in our kitchen, but it has never seen a cornflake or boiled egg. It is the place where I paint the pictures seen in the “From the brush of…” series. But the breakfast bar also has another function. With the full approval of my wonderful wife Mary, it is often converted into a shipyard!

This month’s article features a painting and a model ship, all as a result of the Covid lockdown.

Some time last year I was contacted by Simon Adams, of Southampton. After seeing my articles in Sea Breezes and looking at my website, he discovered that I enjoyed making model ships. I have been building model ships for most of my life.

Simon explained that he had a part-built model of the steel barque “Penang”, started by his father Lloyd Adams in 1935. It hadn’t progressed far beyond the bare hull, and would I like to complete it? Sounded like a good project during the Covid restrictions, so I agreed. I didn’t actually want the completed vessel; I have a house full of model ships, and no room for more, but I would quite happily work on completing “Penang” for Simon.

In May this year Simon was finally able to deliver the vessel to my home, and I started to weigh up the project. I felt honoured to be able to work on this 86-year old model, and felt a responsibility to do as good a job as possible.

Lloyd Adams was passionately interested in deep water sailing ships, and the 1930s were the absolute swan-song of the big cargo-carrying square-rigger. He would write to obtain permission to visit ships in London’s docks, and went aboard several of them. These were vessels owned and operated by the Finnish shipowner Gustav Erikson of Mariehamn. His fleet continued in the Australia/Europe grain trade up to the war.

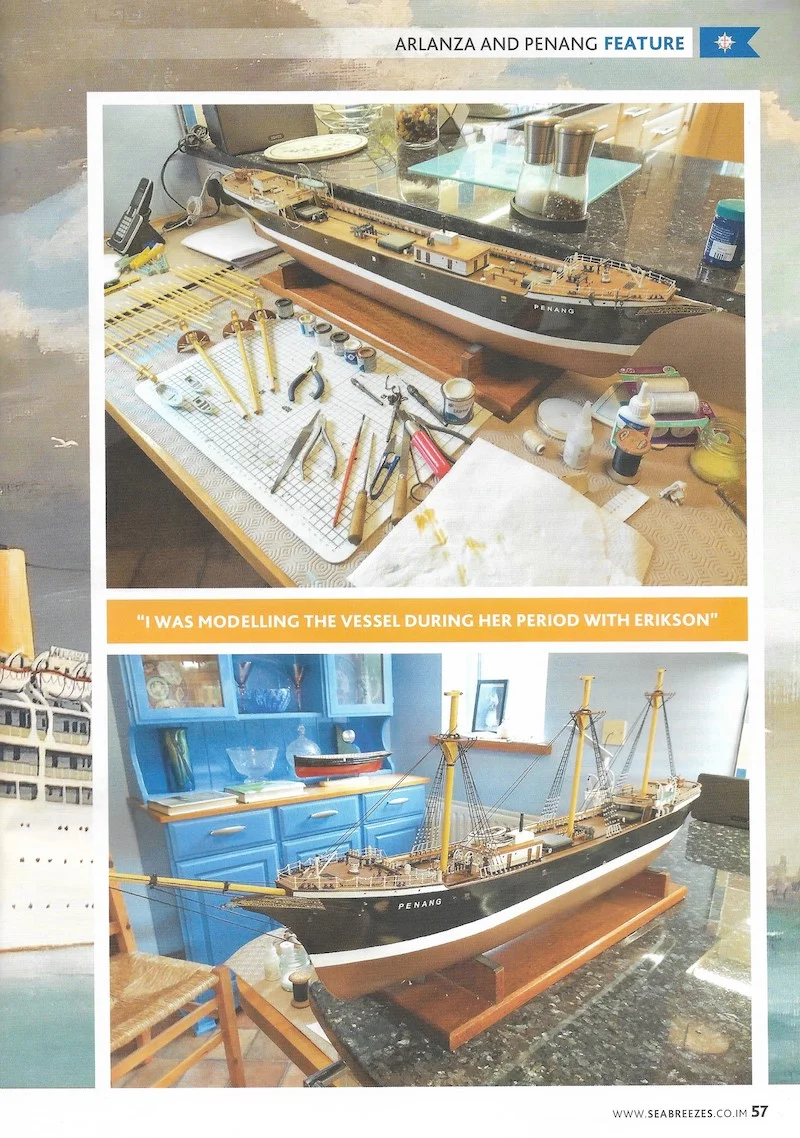

“Penang” was a steel barque built by Rickmers yard in Bremerhaven, as the “Albert Rickmers” in 1905. She was of 2019 gross tons. Sold to F Laiesz in 1910 she was renamed “Penang”, passing to Erikson in 1923. Trading commercially into World War 2, she was torpedoed and sunk with all hands on 8th December 1940.

Plans of the vessel for model-making are available from nautical publishers Brown, Son and Ferguson of Glasgow, as part of the extensive catalogue of plans compiled by maritime historian Harold A Underhill. With the model is a fascinating collection of correspondence between the 15 year old Lloyd, and Underhill. Details of the vessel are discussed, and Underhill gives every assistance to the young builder. He finishes off by asking for a photograph of the finished model in due course.

Harold A Underhill was a remarkable character. He produced detailed drawings of dozens of vessels, mostly sail but some steam; vessels of all types and rigs. His catalogue is a priceless resource of information on ships long gone. He was also the author of a number of books on the subject of working sail, including my “bible” … “Masting and Rigging the Clipper Ship and Ocean Carrier”; an invaluable reference for those modelling 19th and 20th century sailing vessels.

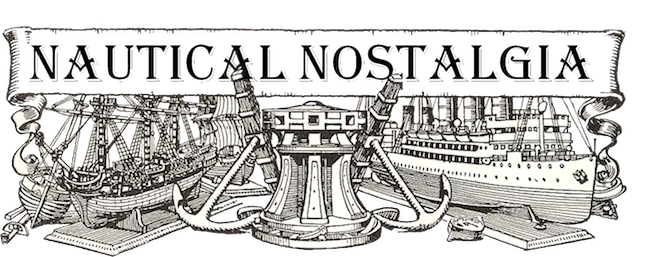

On receipt of the model, I began to realize the enormity of the task in hand. The hull was about 36″ long, and was a completely bare hull. Fortunately, after a lifetime of building model ships, I have a large collection of “bits and pieces” of all types. Dividing the construction into “chunks” seemed to make it a bit easier, and I estimated the task to take about a year.

The outside of the hull was painted, but needed some refurbishment. Decorated trailboards were made and fitted, and the name and port of registry added. I was modelling the vessel during her period with Erikson, as she was when visited by Lloyd. Well-deck next, with hatches, pinrails, dozens of bulwark stays, chainplates for the standing rigging, and a mechanical bilge pump.

Further details applied to forecastle and poop, and the rudder fitted. Four boats, two of which rigged into davits on the poop. She was beginning to look like a ship!

Masts and spars had all been made many years ago, but it was quite a puzzle to determine which was which. Eventually, all were identified, finished and painted. Masts and bowsprit were fitted and rigged – 92 stays!

Great care needed to get the masts upright transversely, and at the correct rake. Error here would be a visual disaster! The final task to date being the ratlines – always a tedious job. Probably another six months to complete the crossing of the yards, and all the running rigging.

The owner of the model, Simon Adams, was an engineer with Royal Mail, and his favourite ships were the “Andes” and “Arlanza”.

Thinking that I probably didn’t have enough to occupy myself with, just his “Penang”, and loads of time on my hands, Simon asked me if I would like to paint “Arlanza” for him, preferably in KGV dock London, accompanied by the tug “Ionia”.

So, the shipyard was dutifully converted back into artist’s studio, and I got on with it (see accompanying “From the brush…”).

While I was so engaged with painting and model building, Simon was busy writing down some of his memories from his Royal Mail days. He, like me, never realized that we were witnessing the very end of an era, and that soon the shipping world would change forever.

Cargo and passenger liners were soon to become a total anachronism in the face of containerization and the jet airliner. Simon’s writings are reproduced below.

An Arlanza Voyage

BY Simon Adams

I joined “Arlanza” as a junior engineer for the first time on 2nd November 1966 in the Victoria Dock, London after she had disembarked passengers and discharged her meat cargo.

From the perspective of a 23-year old looking up from the dockside, she was an impressive sight of some 20,000 tons. Only 6 years old she was in almost pristine condition, white paint and scrubbed teak decks, and the engine room – well almost clean beyond belief after some of the company’s older vessels!

In some ways she was a bit of an anachronism for the time. Three classes of passengers were carried; 1st, cabin and 3rd, together with 5 cargo hatches, mainly for refrigerated meat products, although general cargo could be loaded for outbound trips to South America.

To build 3 such sister ships at a time when it must have been obvious that the liner trade would be soon eclipsed by air travel was possibly a financial gamble to say the least.

Anyway, from the engineer’s perspective she was light years ahead of the other company ships. The engineer’s accommodation was on the upper deck level with a lift down to the upper plate level in the engine room. No gloomy “Burma Road” alleyway and no more counting rivets in the deckhead above your bunk. All the engineer’s cabins were well appointed, and with air conditioning that actually worked. It only needed an en-suite shower and you could have been in a Premier Inn hotel!!

The engineer’s lounge/bar had a wonderful panoramic view aft, over one of the swimming pools down to the stern of the ship to rival anything the passengers might have had! Everybody was encouraged to take a turn behind the bar where a gin and tonic or whisky I think was 6d a generous shot. For some reason, beer was relatively expensive. I seem to remember a bottle of gin at about 10/- (50p), whisky at 12/6 (62½p) but a case of Tennents lager or Mc Ewans was about £1-10s (£1.50).

One peculiarity however of the general layout was the split superstructure design, a throwback to the old “Highland” boats maybe. Obviously, it made access to No.3 hold easier, being between the two superstructures, but in effect it meant that the Captain and officers’ accommodation was remote from ours and as such we had little or no social contact with the deck department at all, very strange after some of the smaller cargo ships where everybody could get together if they wished.

A brief word about the engine room. Two main diesel engines, built by Harland and Wolff to the Burmeister and Wain design, each one of 6 cylinders, opposed piston, single acting 2 stroke, developing some 6000 hp at about 110 rpm. These gave the ship a service speed of a nominal 18 knots, although 18.5 knots was often required to keep to schedule.

Electrical power was provided by 4 diesel alternators, each of about 750 kW. The system was based on AC (alternating current), a welcome change from the older DC ships with open fronted switchboards and a terrifying array of manually operated circuit breakers.

In the case of AC, one only had to adjust the speed of the incoming unit until the 3 phases matched, press a button for the main circuit breaker and bingo – job done. All behind the safety of a closed front switchboard!

The 6-cylinder alternator engines were, I believe, a Harland and Wolff design, 4 stroke with open valve gear. This valve gear only requiring a squirt from an oil can once or twice a watch. Simple and reliable.

The workshop had a pretty decent complement of tools including a nice lathe which I was able to use to good effect during time off, of which more later. It seems strange these days to think that smoking was quite normal in the engine room apart from near the fuel purifiers, a cigarette going down well with a cup of tea made with sticky sweet condensed milk!!

THE VOYAGE

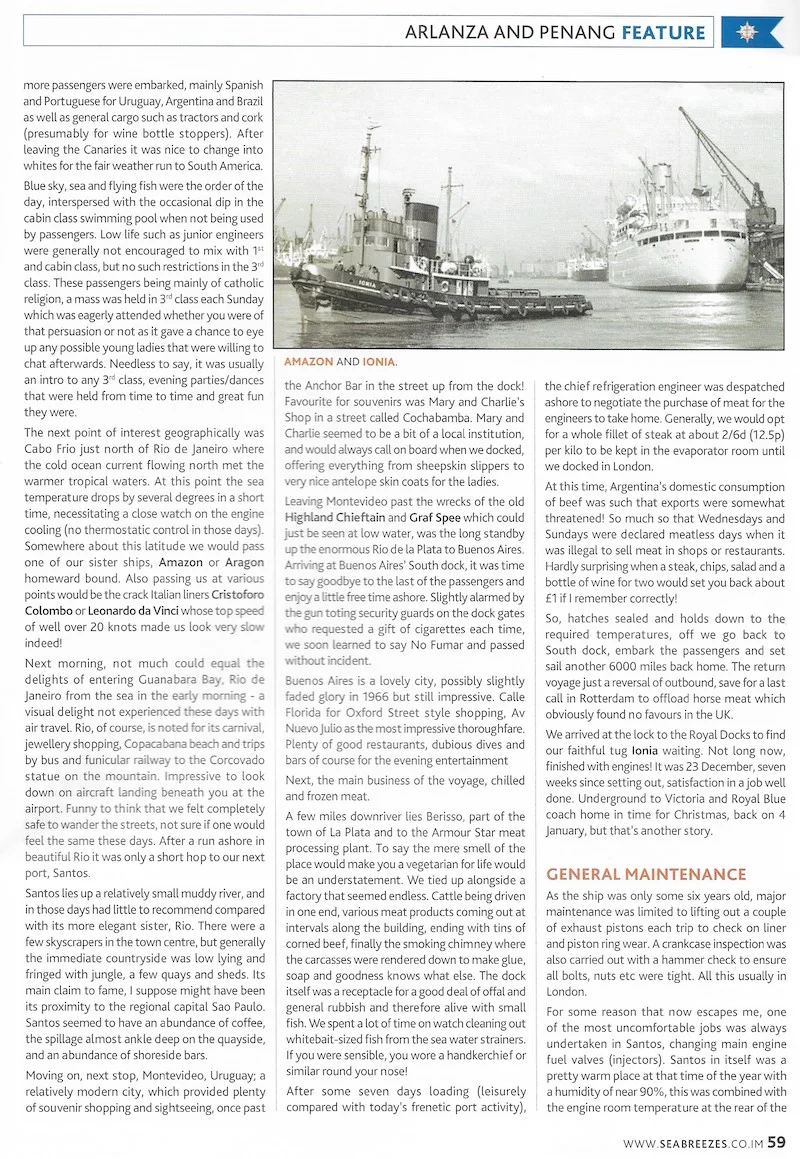

As stated, I joined Arlanza in the Victoria Dock but soon shifted ship to King George 5th Dock or KG5 as it was known. We were ably assisted by the tug “Ionia” which always seemed to be fussing about the Royal docks group generally.

After embarking passengers and pilot with engines still warmed through, we locked out into the London river, still with “Ionia” keeping us in check. The voyage proper had begun.

After clearing the estuary and settling down to sea watches (yours truly on the 12-4) an uneventful trip saw us calling at Vigo, Lisbon and thence to Las Palmas, Grand Canaria, each of these ports for about 1 day. At these stops, more passengers were embarked, mainly Spanish and Portuguese for Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil as well as general cargo such as tractors and cork (presumably for wine bottle stoppers). After leaving the Canaries it was nice to change into “whites” for the fair weather run to South America.

Blue sky, sea and flying fish were the order of the day, interspersed with the occasional dip in the cabin class swimming pool when not being used by passengers. Low life such as junior engineers were generally not encouraged to mix with 1stand cabin class, but no such restrictions in the 3rd class.

These passengers being mainly of catholic religion, a mass was held in 3rd class each Sunday which was eagerly attended whether you were of that persuasion or not as it gave a chance to eye up any possible young ladies that were willing to chat afterwards. Needless to say, it was usually an intro to any 3rd class, evening parties/dances that were held from time to time and great fun they were.

The next point of interest geographically was Cabo Frio just north of Rio de Janeiro where the cold ocean current flowing north met the warmer tropical waters. At this point the sea temperature drops by several degrees in a short time, necessitating a close watch on the engine cooling (no thermostatic control in those days).

Somewhere about this latitude we would pass one of our sister ships, “Amazon” or “Aragon” homeward bound. Also passing us at various points would be the crack Italian liners “Cristoforo Colombo” or “Leonardo da Vinci” whose top speed of well over 20 knots made us look very slow indeed!

Next morning, not much could equal the delights of entering Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro from the sea in the early morning, a visual delight not experienced these days with air travel. Rio of course is noted for its carnival, jewellery shopping, Copacabana beach and trips by bus and funicular railway to the Corcovado statue on the mountain. Impressive to look down on aircraft landing beneath you at the airport. Funny to think that we felt completely safe to wander the streets, not sure if one would feel the same these days. After a run ashore in beautiful Rio it was only a short hop to our next port, Santos.

Santos lies up a relatively small muddy river, and in those days had little to recommend compared with its more elegant sister, Rio. There were a few skyscrapers in the town centre but generally the immediate countryside was low lying and fringed with jungle, a few quays and sheds. Its main claim to fame, I suppose might have been its proximity to the regional capital Sao Paulo. Santos seemed to have an abundance of coffee, the spillage almost ankle deep on the quayside, and an abundance of shoreside bars with the inevitable population of ladies of easy virtue!

Moving on, next stop, Montevideo, Uruguay; a relatively modern city, which provided plenty of souvenir shopping and sightseeing, once past the Anchor Bar in the street up from the dock! Favourite for souvenirs was “Mary and Charlie’s Shop” in a street called Cochabamba. Mary and Charlie seemed to be a bit of a local institution, and would always call on board when we docked, offering everything from sheepskin slippers to very nice antelope skin coats for the ladies.

Leaving Montevideo past the wrecks of the old “Highland Chieftain” and “Graf Spee” which could just be seen at low water, was the long standby up the enormous Rio de la Plata to Buenos Aires. Arriving at Buenos Aires’ South dock, it was time to say goodbye to the last of the passengers and enjoy a little free time ashore. Slightly alarmed by the gun toting security guards on the dock gates who requested a gift of cigarettes each time, we soon learned to say “No Fumar” and passed without incident.

BA is a lovely city, possibly slightly faded glory in 1966 but still impressive. Corrientes for Oxford Street style shopping, Av Nuevo Julio as the most impressive thoroughfare. Plenty of good restaurants, dubious dives and bars of course for the evening entertainment

Next, the main business of the voyage, chilled and frozen meat.

A few miles downriver lies Berisso, part of the town of La Plata and to the Armour Star meat processing plant. To say the mere smell of the place would make you a vegetarian for life would be an understatement. We tied up alongside a factory that seemed endless. Cattle being driven in one end, various meat products coming out at intervals along the building, ending with tins of corned beef, finally the smoking chimney where the carcasses were rendered down to make glue, soap and goodness knows what else. The dock itself was a receptacle for a good deal of offal and general rubbish and therefore alive with small fish. We spent a lot of time on watch cleaning out whitebait-sized fish from the sea water strainers. If you were sensible, you wore a handkerchief or similar round your nose!!

After some 7 days loading (leisurely compared with today’s frenetic port activity), the chief refrigeration engineer was despatched ashore to negotiate the purchase of meat for the engineers to take home. Generally, we would opt for a whole fillet of steak at about 2/6d (12.5p) per kilo to be kept in the evaporator room until we docked in London.

At this time Argentina’s domestic consumption of beef was such that exports were somewhat threatened! So much so that Wednesdays and Sundays were declared “meatless days” when it was illegal to sell meat in shops or restaurants. Hardly surprising when a steak, chips, salad and a bottle of wine for two would set you back about £1 if I remember correctly!

So, hatches sealed and holds down to the required temperatures, off we go back to South dock, embark the passengers and set sail another 6000 miles back home. The return voyage just a reversal of outbound, save for a last call in Rotterdam to offload horse meat which obviously found no favours in the UK.

We arrived at the lock to the Royal Docks to find our faithful tug “Ionia” waiting. Not long now, “finished with engines”! It was 23rd December, 7 weeks since setting out, satisfaction in a job well done. Underground to Victoria and Royal Blue coach home in time for Christmas, back on 4th January, but that’s another story.

GENERAL MAINTENANCE

As the ship was only some 6 years old, major maintenance was limited to lifting out a couple of exhaust pistons each trip to check on liner and piston ring wear. A crankcase inspection was also carried out with a hammer check to ensure all bolts, nuts etc were tight. All this usually in London.

For some reason that now escapes me, one of the most uncomfortable jobs was always undertaken in Santos, changing main engine fuel valves (injectors). Santos in itself was a pretty warm place at that time of the year with a humidity of near 90%, this was combined with the engine room temperature at the rear of the engine underneath the exhaust manifold in the region of 40/45C. The fuel valves weighed in at about 40 Kg and had to be extracted from their pockets with a handy billy and dragged off to the workshop. Spares were then fitted, pipework re-connected and bled through. After changing out 12 of these, we were tempted to try and drink a can of beer for each one! It was the 4th Engineer’s job to overhaul the injectors on the trip home.

Scavenge fires were thankfully a relative rarity, possibly thanks to the Argentinian shore gang giving the scavenge belt a good clean through whilst in La Plata. They arrived in ordinary working clothes (no health and safety in those days), and covered top to toe in hessian sacks for extra protection. After mopping, scraping and a general clean through, it was hard to tell the workers from the heaps of oily rags they collected.

ACCIDENTS AND INCIDENTS

Although remembering the following, these did not, of course, all happen on one single voyage.

I mentioned the incidence of scavenge fires in the main engines which, whilst not that frequent did occur from time to time. There have been many theories as to why they occurred in the B&W design, however too many to examine here. Each unit (cylinder) of the engine was fitted with a fire extinguishing connection and a drain from the scavenge belt which was kept cracked open and dripped into an old gallon can. The first sign of any trouble was either sparks coming from one of the drain cocks, or perhaps the bridge phoning down to say there was more black smoke than usual coming from the funnel. It was only then necessary to identify the source, slow down the engine, and increase the oil supply to that cylinder. A fire extinguisher was then connected and discharged into the offending section of the scavenge belt and the fire would soon be out. Only once I remember did a fire get hot enough to burn the paint on the outside of the engine.

On one trip, the 2nd engineer decided that some job had to be done on one of the overhead cranes above the starboard main engine. In fairly calm tropical conditions, he used a wooden ladder to access the mechanics of the crane which had been moved as far aft as possible. Unfortunately, he obviously omitted to secure the ladder at its top end and during a slight roll of the ship the ladder slipped, depositing him back on the top floorplates with a crash. The ladder meanwhile fell sideways on to the top exhaust piston of No.6 unit where it was demolished into splinters at about 110 rpm! Fortunately, he was not seriously injured but it took a change of underwear and several large gin and tonics before he regained his normal colour and composure!

Another incident of concern involved one of the more senior engineers and took place in Berisso, when it was decided to put an extra turn of packing in the port propeller shaft gland which had been leaking somewhat. After breakfast the gland nuts were released and the gland ring pulled back to expose the stuffing box. 10.30 “smoko” was called so all repaired to the mess for half an hour or so. On going back to the job in hand it was found that the water pressure had been sufficient to start to push the existing gland packing out of the stuffing box. Another occasion for a change of underwear! Fortunately we didn’t sink and nobody was the wiser.

In the time I was on ”Arlanza”, we only had one fairly major breakdown. It was halfway across the Atlantic following the extinguishing of a scavenge fire in the starboard engine when it was discovered that all was not well with one of the units. Sparks were still coming from the drain; the exhaust temperature was a bit high and strange noises were coming from the offending unit. I was not involved in the discussions that followed, suffice to say the chief decided to stop the port engine and open up the unit.

After lifting the top exhaust piston, it was decided to lift the main piston as well. This involved going into the still hot crankcase and releasing the main nut at the base of the piston rod.

The piston and rod, weighing some 6 tons was eventually landed on the top plates and secured. It was evident then that most of the piston rings had seized in their grooves and had to be removed by a variety of unorthodox means I was still on the 12-4 watch and had to keep an eye out for the other engine still running, the other auxiliary machinery and fill in the rough log at the end of the watch. (No computerised data logging system in those days). As we were effectively on “standby”, I stayed on to assist with the breakdown after the 4-8 watch had taken over. After some 16 hours stoppage, the engine was reassembled, and run again without incident.

I mentioned earlier that the workshop served well in my off-duty hours for making pulley blocks for my boat at home. Having obtained a spare piece of teak from the carpenter (chippie) I carved the block with a makeshift chisel and turned up pulleys and spindles on the lathe. It was whilst carving the teak that I stuck the makeshift chisel into my hand. Fortunately, being a passenger ship we carried a nurse and surgeon in the “hospital”. They soon patched me up! Imagine getting a spare piece of teak these days!

In general, the voyage to South America was a fair weather run apart from sometimes when almost home. On one arrival at Rotterdam the weather was appalling with a NW gale such that the pilot service had been suspended and we spent 22 hours steaming up and down the North Sea rolling well!

Anyway, suffice to say I enjoyed my time on “Arlanza” and consider myself fortunate to have sailed on one of the last passenger liner voyages. It was not long before “Arlanza” became “Arawa” under the Shaw Savill flag, then sold again to become a car carrier of all things. Glad I never saw her like that!

Simon Adams

For a full description of the making of the “Penang” model, click here.

For the Sea Breezes article on the “Arlanza’, click here